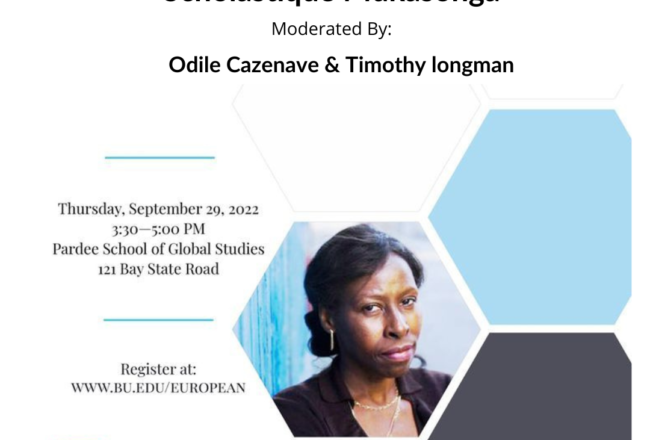

To get a precise idea of Bugesera, where this story happened, I selected for you some pics and excerpts inspired from my book ” Cockroaches ” translated from French by Jordan Stump and published on Archipelago Books.

In 1958, sub-chief Ruvebana was appointed to Butare province, and my family followed him. The sub-chiefdom was located in the far south of the province, on the crests overlooking the valley of the Kanyaru, whose course forms the border with Burundi. From our new house, in Magi, on the steep foothills of Mount Makwaza, we had a sweeping view: the valley of the Kanyaru and its papyrus swamps, and, beyond, much of the Ngozi province in Burundi.

(pp. 12)

My big sister Alexia and my older brothers Antoine and André went to school. My mother worked in the fields. We rarely saw my father at home; he had an office, which still exists, facing the sub-chief’s residence, but he didn’t spend much time there, because he was always out on his bicycle seeing to matters that I found deeply mysterious. My father had the only bicycle in the area, which gave him considerable prestige, reinforced by the pen sticking out of his shirt pocket, an uncontested sign of his authority.

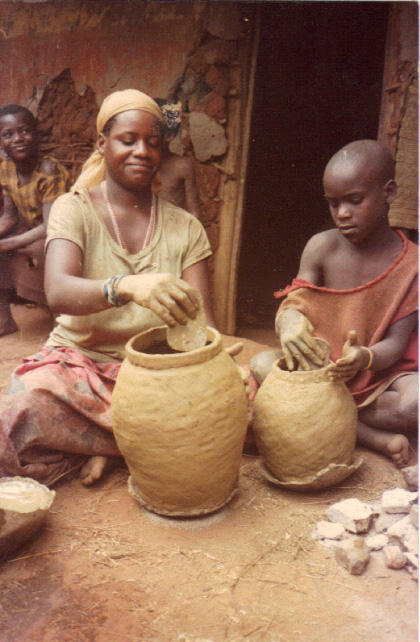

As for me, I spent my days with the potters who’d set up their camp in the eucalyptus woods facing the house. They were Batwa, a people kept at arm’s length by the rest of Rwanda. The first Euro¬peans called them Pygmies, very wrongly. Boniface, the patriarch of the “tribe,” welcomed me as if I were his own daughter, and my mother thought nothing of seeing me go off to play with the chil¬dren of people traditionally treated as pariahs. She often gave me beans and sweet potatoes for the children, and in return the Batwa brought her their nicest pots. (pp. 13)

The first pogroms against the Tutsis broke out on All Saints’ Day, 1959. The machinery of the genocide had been set into motion. It would never stop. Until the final solution,

it would never stop.

Needless to say, the anti-Tutsi violence didn’t spare Butare prov¬ince. I was three years old, and that was when the first images of terror were etched into my memory. I remember. My brothers and my sister were at school. I was at home with my mother. All at once we saw plumes of smoke everywhere, rising up from the slopes of Mount Makwaza, from the valley of the Rususa, where Ruvebana’s mother Suzanne, who was like a grandmother to me, had a house. And then we heard noises, shouts, a hum like a swarm of monstrous bees, a growl that filled the air. I can still hear that growl today, like a threat rising up toward me. Sometimes I hear that growl in France, in the street; I don’t dare turn around, I walk faster, isn’t it that same roar, forever following me? (pp. 15)

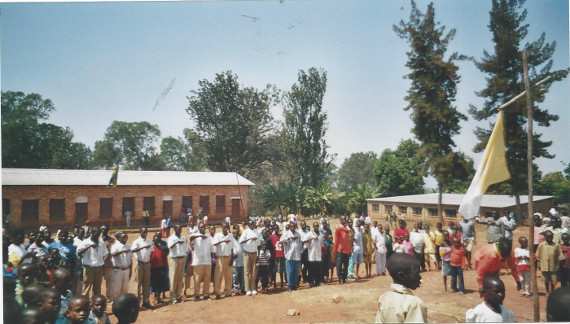

The refugees were housed in Mugombwa church and the class¬rooms of the mission. They stayed there for some two weeks.

On Sundays the church is full. How many murder¬ers among the pious assembly? The faithful sing with all their hearts. Jesus is kind. He forgives all sins. He forgets everything. When Mass is over, the young people from a Catholic movement raise the Vati¬can’s gold and white flag, marked with the Chi-Rho symbol. Hand on heart, they sing a hymn to the glory of Saint François Xavier. Who would ever be so tasteless as to bring up the “unfortunate events,” as they’re called by those who deny all participation in the genocide and refuse to speak the word? Let us forgive each other, and let us go on as if nothing had happened. (pp. 17-18)

It was on Rebero hill that most of the inhabitants of Gitwe, Gita¬gata, and Cyohoha gathered to defend themselves from the murder¬ous mob. That came on the 11th, 12th,

and 13th of April.For two days, the people who’d got to Rebero held off their attackers. Once they’d built the women and children a shelter among the eucalyptus trees, the men took up sharp Rebero stones to fight back their killers’ machetes. Unable to manage on their own, the Interahamwe militia and Hutu mobs from Gashora and Ngenda asked the soldiers from Gako for help; the soldiers sprayed the hill with fragmentation grenades, and then the hordes of ordinary killers finished the job with machetes.

No memorial has been built on Rebero. Nothing to commemo¬rate the fallen but boulders and white and rust-red stones. I look for signs from the hill, I dig at the ground. The sun is straight overhead. This is the hour of mirages. I push away the little rocks, I scratch at the ground. I find a shred of tattered cloth half-buried in the dirt. I try to convince myself that it comes from Antoine’s shirt. (pp. 143)

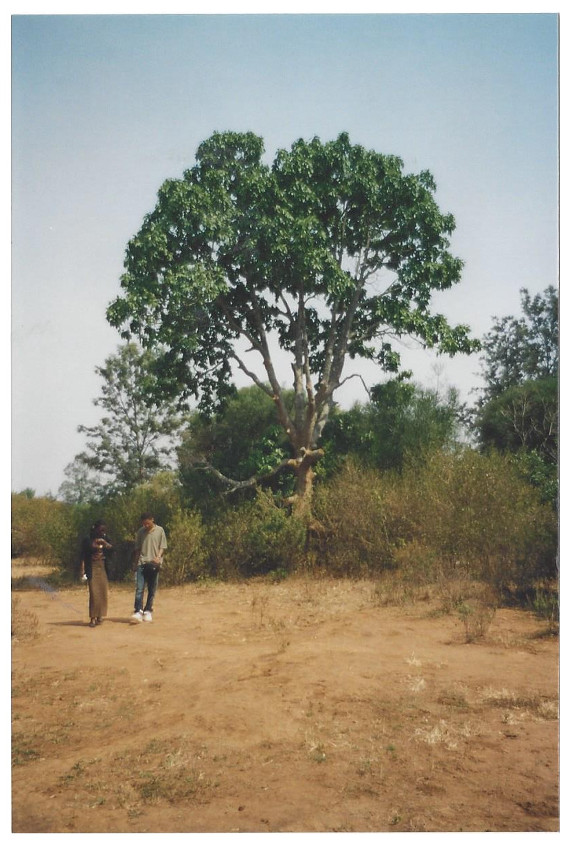

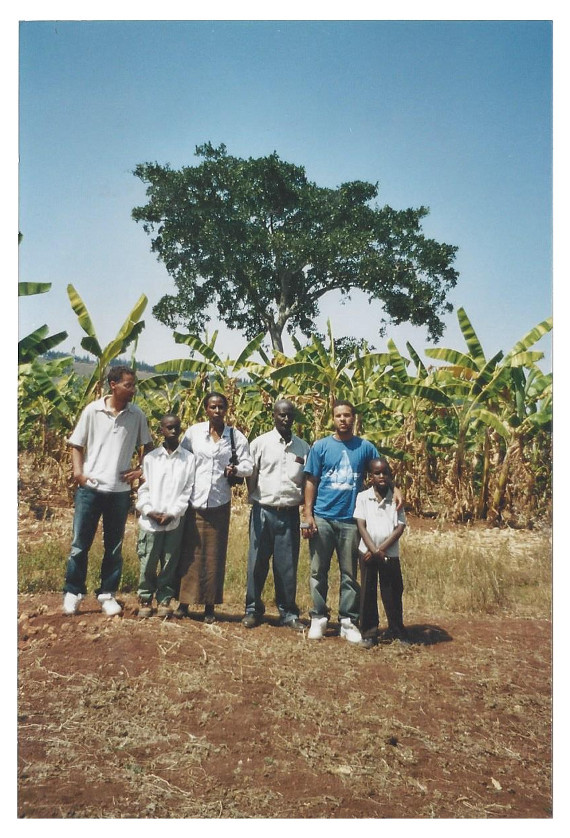

In the bush, now brown with the dry season, what was once Antoine’s yard is easy to make out. It’s the only one with big trees whose leaves are still green, looking strangely exotic amid the thorny undergrowth. He planted them with the seeds he brought home from the Karama Agricultural Institute. He loved them. He took special care of them. I kneel at their feet.

I weep at the feet of the tall trees. (pp. 152)

The truck has stopped. To the left of the road, still the same tangle of bushes, of thickets. “Look,” Emmanuel says to me, “don’t you recognize it? That’s Cosma’s place, and Stefania’s, that’s where you lived!” I look at the tangled mass of brush, I have a hard time convinc¬ing myself: this is where I lived! “Look,” Emmanuel goes on, “there are the sisal plants at the entrance!” Yes, at the edge of the road, there are indeed a few browned leaves, with black spines, slightly withered by the dry weather. Emmanuel points to a tree smothered by brambles and vines: “There’s Jeanne’s avocado tree!” This is my home, I tell myself over and over, and I realize that, to protect myself, despite everything my brother had told me, everything I knew, I’d clung to the illusion, like a deep secret hope, that the ruination of Gitagata had spared something in the place where I lived, that some sign was awaiting me from beyond death’s domain. But of course there was no one and nothing. And suddenly I began to violently hate the untamed vegetation that had so efficiently finished the murder¬ers’ “work,” that had turned my home into this inhospitable patch of brush.

(pp. 160)

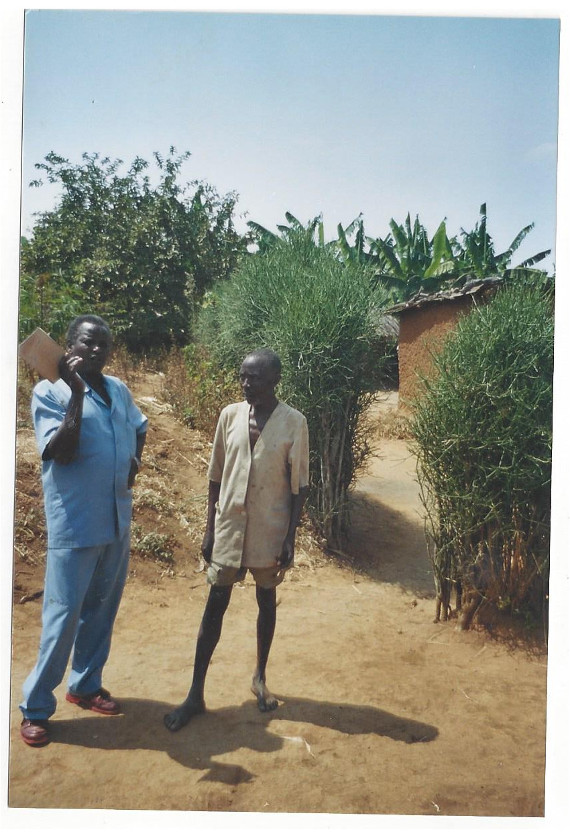

“Listen,” Emmanuel says to him, “this is Cosma’s daughter in front of you,

do you have anything to say to her?”

A long silence. He hesitates.

“Yes, that’s Cosma’s daughter, now that I see her, I can certainly ask for her forgiveness . . . ”

I stand glued to the spot, half-paralyzed, stunned by these words. Another long silence, and then I search in vain for some way of encouraging him to go on, to tell me what I’ve so long wanted to know . . . but it’s already too late, he’s gone back to his denials,

I’ll get nothing more out of him.

“Listen, I never killed anyone, they went up there to Rebero, I didn’t kill anyone. It was around four in the afternoon when they left, I remember. I didn’t kill anyone. Have you ever heard anyone say I did? The family died on Rebero. They were old. No one died here. I never met his children, except for that day he married off his last daughter . . . ”

(pp. 163)

I look at the tall fig tree. No, the killers hadn’t succeeded. My two sons are alive. They’ve seen the tall fig tree that preserves the memories, and like that tree they’ll remember. (pp. 16)

No Comment